Class starts tomorrow.

Here’s the tl;dr.

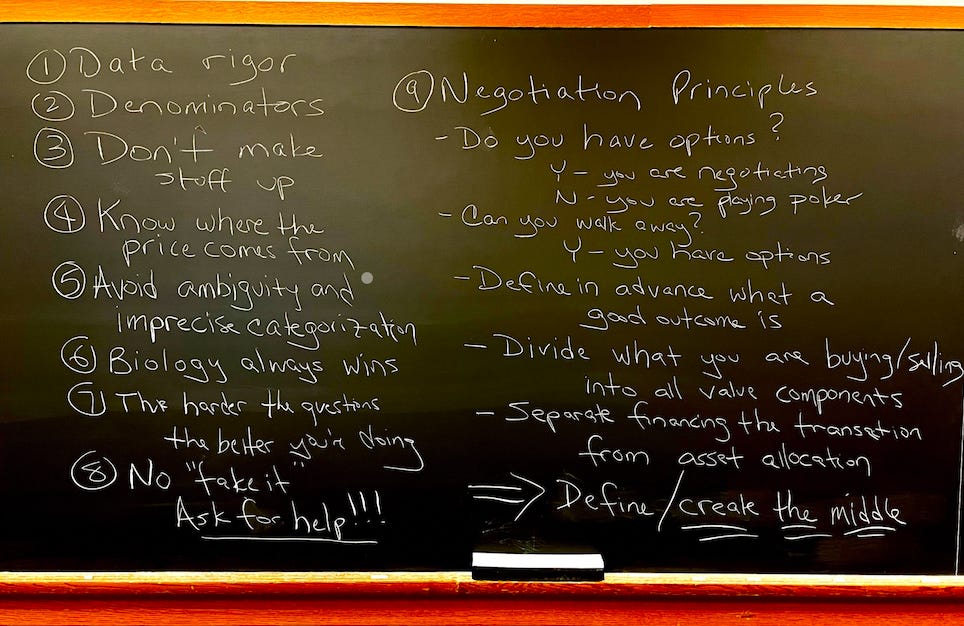

You are only as good as your data.

Numbers need other numbers to be meaningful.

Don’t Make Shit Up.

Know Where Your Price Comes From.

Develop a sixth sense for ambiguity and meaningless categories.

BIOLOGY ALWAYS WINS.

Embrace being asked difficult questions — they define your path forward.

NONE OF THIS FAKE IT ‘TIL YOU MAKE IT. THIS IS HEALTHCARE!

Know. How. To. Negotiate.

(More rules to come.)

Let’s start.

A biotech company is two organizations. There is a medical science organization that runs experiments of increasing complexity, gradually demonstrating that a newly discovered or synthesized molecule, or uniquely repackaged or delivered molecule, or two or more drugs stuck together in some way, can carry out a mission when introduced into the body — a mission that relieves pain or dysfunction or cures disease.

The second half of the company raises and spends money to support the first.

Drug development is long, complex, and expensive, and gets more expensive the more progress the company makes. Idea generation costs less than running cell culture experiments, which are cheaper than animal experiments. Human (clinical) experiments cost far more than preclinical, and the costs accelerate rapidly from Phase 1 through Phase 3.

During this multi-year process, the project generates no income, so the company needs to serially raise greater and greater amounts of money, each “ask” based on the demonstration of progress towards the development of a drug.

For most businesses, proof of concept relies on revenue and cash flows, numbers that are fairly straightforward to calculate and communicate, which can then be used in simple equations that both buyer and seller use to come up with a valuation, the basis of a transaction to sell or buy a piece of the company, either privately as venture capital or publicly as common stock.

In biotech, revenues are years away, so progress in drug development serves as a substitute for financial metrics. In these cases, the connection between moving from one step to the next, and the value created in doing so, can vary a lot depending on who is doing the calculations.

About mid-way through a biotech pitch deck, the proof of concept slides reside. But one person’s proof of concept is another’s suggestion of concept, yet another person’s mildly interesting factoid that doesn’t really prove anything, and another’s totally irrelevant distraction with an easily disproven relevance.

In our shop, we call it the So What test.

Lots more to come…

See you tomorrow morning: Uris Hall, Columbia University.